UNT's CLAW 3 Active Learning Classroom Instructional Guide

- DSI CLEAR

- Teaching Resources

- Theory & Practice

- Methods for Continuous Improvement

- Using AI in the Higher Education Classroom

- Invisible Labor and Faculty Retention Since COVID-19

- Inclusive Discussions

- Inclusive Assessment

- Designing Assessments for Academic Integrity

- Inclusive Instructional Strategies

- Instructor Presence in the Online Classroom

- Tips for Providing Personalized Feedback to Students

- Course Design for Student Retention

- UNT's CLAW 3 Active Learning Classroom Instructional Guide

- UNT Faculty Teaching & Learning Resource Guide

- Growth Mindset in the Higher Education Classroom

- Course Outcomes & Objectives

- Multimedia Course Design for Student Engagement and Retention

- Level Up Learning With Portfolios

- Group Work in Higher Education: Benefits & Practices for Success

- Open Educational Resources & Copyright Essentials for Instructors

- Evaluating OER Resources

- Accessibility Online

- Copyright Guide

- Online Teaching

- UNT Syllabus Template

- Teaching Consultation Request

- Open Educational Resources & Copyright Essentials for Instructors

- Evaluating OER Resources

UNT's CLAW 3 Active Learning Classroom Instructional Guide

Introduction

This guide to teaching in CLAW (Collaborative Learning and Active Workspaces) 3 Active Learning Classrooms (ALCs) reviews the recent literature on the experience and impact of teaching and learning in ALCs. Suggestions for teaching strategies and activity ideas are included. Please contact dsitech@unt.edu for questions about UNT’s CLAW 3 classrooms. Instructional technology videos can be found on the UNT DSI Tech Youtube channel.

What is Active Learning?

Broadly speaking, active learning is defined as doing and thinking about doing (Bonwell & Eison, 1991). Students are actively engaged in the learning process and applying higher order thinking skills. Active learning is an important component of teaching in ALCs, but the room itself also contributes.

What is an Active Learning Classroom?

Active learning classrooms (ALCs) are intentionally designed for the purpose of active learning (Talbert & Mor-Avi, 2019). Group work is emphasized in the layout of UNT’s CLAW 3 classrooms. One way to think about group stations in CLAW 3 classrooms is as in-person version of “break out rooms” in virtual meetings. It has also been suggested that they remind instructors and students of the cozy feeling of sitting around a kitchen table (Copridge, 2021).

In addition to a projection screen and document camera for the instructor to display

information to the whole class, each group station has a screen and connection that

allow students to display information in their small groups. Instrumental in creating

a collaborative group experience, CLAW 3 rooms are designed with movable tables and

chairs. These tables are in groups of four or eight students, each with a wall display

(Figure 1).

Figure 1

CLAW 3 Room in Sage 230

There are three CLAW 3 classrooms on the UNT Denton campus (Table 1).

Table 1

UNT CLAW 3 Rooms

|

Room Location/Layout |

Room Capacity |

|

46 |

|

|

72 |

|

|

32 |

Why teach in ALCs?

There are many reasons to teach in an ALC. The most compelling is the relationship between ALCs and active learning. Practicing active learning teaching strategies in an ACL encourages discussion, active participation, critical thinking, collaboration, community, fun, and a desire to attend class (Allsop et al., 2020; Clinton & Wilson, 2019; Holec & Marynowski, 2020; Lee, et al., 2019; Rezaei 2020; Stalph & Hill, 2019; Young et al., 2021). After a semester in an ACL, 93% of 434 students surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that group activities in class help them learn (Stalp & Hill, 2019). In a survey of 916 students, 86% reported learning better in ALCs, 98% said that they encourage teamwork and cooperation, and 80% felt they had more time to ask questions (Rezaei, 2020).

ALCs also improve other aspects of the student learning experience. In a large-scale longitudinal study of 30,000 students over four years, students across all disciplines felt that course content was less difficult in ALCs (Chiu et al., 2022). However, other perceptions of learning in ALCs were found to fluctuate across different academic disciplines. Students in the sciences, technologies, arts, and humanities related significantly better experiences in course design, the encouragement of innovation and creativity, and the support of critical thinking. Business organization courses deviated from these findings. In other words, learning experiences were not perceived by students as positively in these areas in business organization courses. These findings indicate possible interactions between academic discipline and the impact of teaching in ALCs.

ALCs change the way that instructors and students engage. With the increased mobility of the instructor and a decreased emphasis on the front of the room, students perceive instructors to have a less authoritative role (Rezaei, 2020). Instructors’ role in the ALC is to circulate while facilitating group thinking and bringing examples to the whole class (Rands & Gansemer-Topf, 2017). This enhances student–teacher interaction and dialogue and, over time, can lead to improvement in learning and students’ sense of belonging (Rands & Gansemer-Topf, 2017). Nine instructors who taught in ALCs for a year reported that the grouped tables and movable chairs created a more intimate and “cozy” environment (Copridge, 2021). Additionally, a study comparing 372 students in ACLs and traditional classrooms found in improvement in self-confidence among female students (Mantooth, 2021).

The Impact of ALCs on Introverts and Students with Anxiety

Studies have found that ALCs can positively impact learning for introverts and students with anxiety. A two-year study of 266 students by Flanagan & Addy (2019) found that introvert, ambivert, and extrovert students performed equally in classes using a team-based and flipped learning approach, all reporting high levels of support.

At the beginning of the semester, ACLs can feel uncomfortable or anxiety-inducing to students since the focal point is not on the instructor as in traditional lecture halls. Students who are used to sitting in the back of the classroom may be disoriented at first to find that there is no back in an ALC. However, a study by Baepler (2021) found that the roundtable design helped reduce anxiety because it places the focus on the material. Students reported that once they got used to the roundtable format, it increased engagement and focus and reduced anxiety.

Recommendations from Baepler (2021) for teaching introverted students and students with anxiety in ALCs follow:

- Verbally acknowledge the ambient sound in an ALC.

- Dim lights and request monitors to be turned off when not in use.

- Allow “chaos” during group work but call for intervals of quiet.

- Encourage students with anxiety to sit near a door so they have easy access to an exit.

- Move around the room and be near students often.

- Create a way for students to ask questions (raise hands, call lights, etc).

- Flip the class by providing readings, video, and recorded lectures to allow students to examine content before class without distractions. It also gives students with anxiety or processing disorders more time to formulate questions.

- If using flipped learning, give students time at the beginning of each class to discuss the content with classmates.

The Impact of ALCs on Teaching

Teaching in an ALC can impact the way instructors teach. Findings indicate that ALCs lead to increased instructor presence and visibility, better feedback to students, and more authentic discussions between instructor and student (Copridge, 2021). In a survey of 53 instructors, 58% reported lecturing less in the ALC than traditional classrooms, and 39% said that ALCs help them get better feedback from students (Rezaei, 2020).

Why to Attend Training on ALC Teaching

The first step toward adopting an active learning mindset is to schedule one of the CLAW 3 classrooms. However, the room alone will not guarantee that active learning will ensue. Gains in learning are made when instructors learn teaching methods that are effective in the ALC (Lee, et al., 2019). The literature encourages instructors to attend teaching and learning workshops to develop teaching methods and activities designed specifically for the ALC (Lee, et al., 2019). This literature review, along with DSI’s CLAW 3 Orientation is offered with that goal in mind.

Learning gains are made when the classroom, teaching style, and academic discipline align. When active learning strategies are used in lecture-style classrooms, for instance, students do not self-report the same high levels of engagement (Holec & Marynowski, 2020). Conversely, a study of computer science courses found that active learning and teaching improved academic performance, but the ALC was not found to be a contributing factor (Hao, et al., 2021). As mentioned earlier, business organization students in a study by Chiu et al. (2022) did not report as enjoyable an experience in ALCs as students in other academic disciplines. Therefore, teaching strategies, classroom, and subject will interact uniquely (Hao, et al., 2021).

Another reason why training is important is because teaching in an ACL requires some course redesign (Razaei, 2020). Instructors may be encouraged to know that redesign does not need to happen overnight. It can happen incrementally, making small changes each semester.

Razaei (2020) surveyed 53 instructors who taught in ALCs and found that while more than 70% had never observed another instructor teaching in an ALC, it could greatly improve their practice. Observing others teach allows instructors new to ALCs to see how the technology is used in addition to learning andragogical strategies. Instructors can also observe how others prepare students for learning in ALCs, including technology use and norms around group participation.

Another reason to prioritize learning active learning techniques in ACLs is because instructors tend to be less likely to innovate in ALCs when they feel uncomfortable with new technology or layouts. In a study by Murphy (2020), an instructor restructured the entire class to avoid using a piece of technology that they did not know how to use. Training that includes time to practice along with on-call support can help prevent use avoidance.

McCorkle (2021) suggests that the following can act as barriers to the implementation of active learning approaches in ALCs:

- Time – Instructional preparation time is the biggest barrier to the practice of active learning. Instructors spend years developing lectures and materials, and redesigning for an ACL takes time. Also, active learning activities often take longer, which changes the way class time is used. The literature recommends making small, incremental changes.

- Faculty development – Orientations and ongoing professional development can help instructors learn how to implement student-centered, active learning practices. ACL peer communities have been more successful than one-off workshops.

- Role and value – The shift from lecturer to facilitator can be uncomfortable for instructors. It can be helpful to pair new instructors with those more experienced in ALCs. It can also help if this is encouraged at the departmental level.

DSI CLEAR offers resources, training, and learning communities in addition to these recommendations from the literature to help instructors effectively use ALCs and active learning strategies.

Strategies for Teaching in ALCs

This section reviews recent literature on engagement types, assignments, tools and features, and classroom management to help you prepare to teach effectively in ALCs.

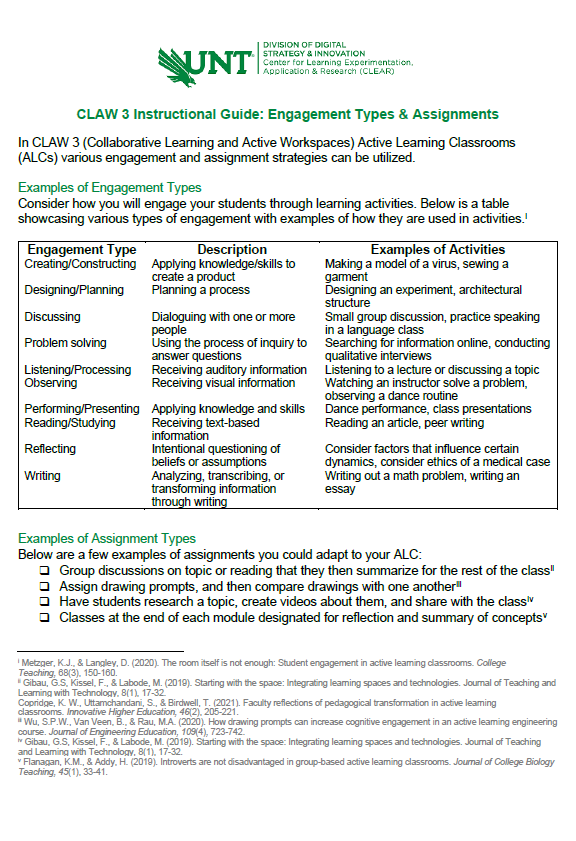

Engagement Types

When redesigning classes to teach in ALCs, it can be helpful to review the types of engagement that make up teaching and learning activities.

Metzger & Langley (2020) conducted 45 observations of 23 courses. In any one class meeting, 2-8 engagement types were used with an average of 4.9 per class. This held true regardless of course level and discipline. The complete list of engagement types from the Metzger & Langley (2020) study with examples is provided in Table 2.

Table 2

Classroom Engagement Types

| Engagement type | Description | Activity examples |

| Creating/Constructing |

Applying knowledge/skills to create a product |

Making a model of a virus; sewing a garment; painting a picture |

| Designing/Planning |

Planning a process |

Designing an experiment, architectural structure, or prosthetic limb |

| Discussing |

Dialoguing in-person or digitally with one or more people |

Think/pair/share; small group discussion about the meaning of a reading; practicing speaking in a language class |

| Problem solving |

Using the process of inquiry to answer a question |

Combining reactants in a chemistry lab; searching for information online; conducting qualitative interviews; diagnosing medical issues |

| Listening/Processing |

Receiving auditory information |

Listening to an instructor lecture on a topic or talk through a problem |

| Observing |

Receiving visual information |

Watching an instructor solve a problem on the board; watching a video of children playing; observing a dance routine |

| Performing/Presenting |

Applying knowledge and skills |

Music or dance performance; acting out a play; public speaking, performing a procedure |

| Reading/Studying |

Receiving text-based information |

Reading a book, article, procedures, or peer writing |

| Reflecting |

Intentional questioning of existing beliefs or assumptions |

Considering ethical beliefs in the context of a medical case; thinking about how one’s personality might influence group dynamics; writing or talking about how your background impacted your choice of college major |

| Writing |

Analyzing, transcribing, or transforming information through writing |

Drawing a table on a whiteboard; writing out the solution to a math problem; writing a paper, essay, or report, taking lecture notes |

Note. Adapted from “The room itself is not enough: Student engagement in active learning classrooms” in College Teaching by K.J. Metzger, & D. Langley, 2020, 68(3) p. 150-160.

While creating/constructing and performing/presenting were never observed in the Metzger & Langley (2020) study, listening/processing, discussion, and problem solving made up almost 75% of all classroom time.

When deciding how to distribute engagement types over a class session, it might be helpful to keep in mind that due to the group-centered layout, ALCs encourage group interaction and discourage instructor-focused whole class discussion. A two-year study of 266 students by Flanagan & Addy (2019) found that students work collaboratively for more than 50% of classes. Similarly, in a study of 14 class sessions over four semesters, class time was spent as follows (Bent et al., 2020):

- Small group activities (49%)

- Listening (33%)

- Individual activities (12%)

- Whole class discussion (6%)

Therefore, activities that employ peer and small-group discussion and collaboration are likely to be successful in ALCs. In a survey of 916 students, 93% believed that frequent peer discussions helped them learn (Rezaei, 2020). That is not to say that whole class discussions do not have a place in the ALC. Students in Rezaei’s (2020) study said they missed whole class discussions. This can be remedied by following individual or group activities with whole class discussions to debrief activities together.

Assignments

This section lists specific assignment strategies from the literature that instructors may be able to adapt for their own classes in an ALC.

- Student-led discussions: Assign a research article for groups to discuss. A student facilitator at each table leads the discussions (Gibau et al., 2019).

- Students research the content: If instructors are transitioning from a lecture-style class to teaching in an ALC, a time-saving way to make the class session more interactive is to take one or two of the central themes from your lecture and ask students to go online and find the content themselves. It may take longer, but students will be more actively engaged than listening to lectures. Follow with discussion and publicly documenting or wall/board activities listed below (Chacon-Diaz, 2020).

- Discuss & publicly document: Students discuss a topic, and then summarize what they discussed on the screen or board at their group station. This allows students to reflect and peer-review the thinking that occurred in the discussions (Birdwell, 2018). It also provides a multi-modal way to access the discussion, increasing access to learning (Gibau et al., 2019).

- Drawing to demonstrate understanding: Students draw concepts and then compare drawings with group members. Instructors give targeted drawing prompts and offer guidance on what to draw to solve specific problems. This practice of drawing to understand engineering concepts improved exam scores (Wu et al., 2020).

- Research videos: Students research a topic, create videos about them, and share them with the class in person or in a learning management system (Gibau et al., 2019).

- Scavenger hunt: Students take pictures of examples of how course content shows up in the world and use ALC technology to show the group or class what they found (Gibau et al., 2019).

- Wall/board activities: The instructor asks a question, and students take turns going to the board to write a response. Students compare answers with others before writing their response. Examples of answer types can be defining terms/concepts or drawing pictures/graphs. Seated group members can provide guidance for those writing the answer at the board. A case study of 28 students in an introductory biology course showed that engagement was high for the student writing the answer on the board, but seated students would sometimes engage in off-topic activities (Chacon-Diaz, 2020). Some students would also resist the activity by not wanting to be the one to write on the board.

- Role-play: Group seating is perfect for role-play to practice applying skills. Social work students practiced communication skills for clinical practice through role-play in ALCs (Holec & Marynowski, 2020).

- Pop-up museum assignment: Students select a topic, research it, and identify three objects associated with that topic. Students display those objects in an exhibit, demonstrating what they illustrate about the topic on classroom screens (Gibau et al., 2019).

- Flipped classes: Students read or watch content before class, allowing time to be spent on discussing, collaborating, or applying (Razaei, 2020). Flipped learning has been found to lead to improved learning outcomes than in lecture-based classes (Chih-Yuan Sun & Wu, 2016; Kugler et al., 2019).

- Student-authored quizzes: Students read and prepare for the unit outside of class. In class, students write a quiz on the content, then the class takes the quiz. The instructor prepares lectures to fill in the gaps based on the results of the quiz (Flanagan & Addy, 2019).

- Clicker questions: Students listen to lecture and use clickers to respond to multiple-choice questions while discussing the answers with peers. A case study of 28 students in an introductory biology course showed that engagement with clickers was high, but the motivation was more about getting the answer right than engaging with the content (Chacon-Diaz, 2020).

- Groupwork grades: Peers grade group participation (Flanagan & Addy, 2019). In a survey of 916 students, 58% believed that the face-to-face nature of the ALC prevented “free riders” in group work (Rezaei 2020).

- Case study worksheets: Students read or watch a description of a relevant case study, ask and answer questions about the case study in small groups, and then present their ideas to the larger group and engage in whole class discussion. In a biology class with 28 students, 100% of students remained on-task when solving case studies (Chacon-Diaz, 2020).

- Practice and analyze: Students can demonstrate a practice, or “rich task,” they will be asked to do in their career. This is followed by a “metacognitive conversation” to processes and analyzes the activity (Holec & Marynowski, 2020, p. 148).

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: Three instructors created a learning community out of three different classes (Gibaun et al., 2019). The classes that took part in the community were Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, Understanding Museums, and a First Year Success Seminar. Classes took turns visiting each other and engaging in interdisciplinary activities.

- Reflection classes: Each unit or module ends with a reflection or summary class before moving on to the next unit (Flanagan & Addy, 2019).

Additional Assignment Resources.

- The National Institution for Learning Outcomes and Assessment (NILOA) Assignment Library houses higher education classroom assignments that have undergone a three-part review process.

- The University of Minnesota’s Center for Educational Innovation has a guide on teaching in ALCs.

Classroom Tools and Features

ALCs are intentionally designed to support active learning. Becoming familiar with the features of ALCs can help optimize the teaching and learning experience (Murphy, 2020). This section will review literature about how to use the features of ALCs.

Technology is often a feature of the ALCs, and students expect it to be used (Stalp & Hill, 2019). However, what appears repeatedly in the literature is that classes should be designed with andragogy, or how adults best learn, at the forefront. Technology should be used to support teaching and learning, not the other way around (McCorkle, 2021; Murphy 2020; Razaei, 2020).

A study by Stalp & Hill (2019) found that students who started the semester uncomfortable with technology were not made more comfortable by simply being in the ALC. Comfort with technology stayed the same throughout the semester. Instructors can help improve the student experience in ALCs by directly addressing attitudes around the ACL and its technology.

A study by Fukuzawa and Cahn (2019) found that students found some technology in an ACL helpful and some a hindrance. For instance, most students found the overhead camera, roundtables, and whiteboards useful in an osteology course. However, more than half found the accompanying discussion boards unmotivating and not additive. Students in a study by Razaei (2020) reported not using the large TV at their station very often in their group work, but they did appreciate that the instructor’s screen could project on their group station screen.

The literature highlights the following uses of technology and space in ALCs:

- Students believe that 5-6 students per table is ideal (Rezaei, 2020).

- Students prefer the instructor to be in the center of class rather than the front (Razaei, 2020).

- Moveable furniture opens floor space for community-building activities (Gibau et al., 2019).

- Whiteboards can be used by students to process and reflect on groupwork and discussions (Gibau et al., 2019).

- Instructors often use the large monitor at each table to share group work with the entire class (Rezaei, 2020).

ALCs can have a novelty effect that can improve learning in the short-term but wears off over the course of the semester (Razaei, 2020). Instructors can remedy this by connecting their teaching philosophy and approaches to the ALC environment, explaining the benefits of the room to students. Regardless, some students will find the ALC a positive learning experience and others may not. For instance, noise can be a distraction for students and instructors (Rezaei, 2020). Scheduling quiet work times can help balance the noise. Instructors can also remind students to lower their voices. Too many screens may also make it difficult for some students to focus (Murphy, 2020). A solution is to schedule screen-off times while students are focusing. Distraction from screens and noise are why students in smaller ALCs report more satisfaction than students in larger rooms (Rezaei, 2020).

The Murphy (2020) study found that instructors and students prefer low-tech learning such as group work and discussion. They recommend that new ALC instructors focus on utilizing the group tables and should not feel pressured to use all the technology. In fact, the goal of ALCs is communication and human connection, making it an ideal setting for providing students opportunities to practice interaction and soft skills that will make them successful in their future careers and endeavors (Lee et al., 2019; Stalph & Hill, 2019).

Classroom Management

ACLs change instructor-student dynamics. In a traditional lecture classroom, the instructor is positioned as the provider of information at the front of the room. In ALCs instruction is dynamic in that it moves around the classroom, and the instructor is often at the middle or back of the class. Furthermore, students often facilitate their own group activities without direct, step-by-step instruction from the instructor. This can change some aspects of how instructors manage their classrooms. This section highlights considerations about classroom management in ALCs:

- Instructor circulation: Best practice is to approach each table at least once during each class period (McCorkle, 2021).

- Seating arrangements: Decide if you will assign seating or let students choose. If assigned, it is recommended to give students the choice to change seating during the semester. Instructors can also ask students to get up and move during class depending on the activities (McCorkle, 2021).

- Establish ground rules: Instructors with experience teaching in ALCs recommend clearly stating the class rules at the beginning of each semester (Razaei, 2020). Examples of class rules included expectations of students, expectations of instructor, how to ask questions, etc.

- Dealing with distraction: Experienced ALC instructors recommend preemptively expecting distractions caused by

noise and off-task students (Razaei, 2020). Additional recommendations include:

- Move toward or stand near distracted students.

- Plan for group work to be graded by their peers, group facilitator, or instructor.

- Give time limits on activities.

- Assign assistants or facilitators.

- Ask random students to summarize or report on the group discussion.

- Centralized instructor station: Positioning the instructor in the center can help democratize the higher education classroom. In a study by Razaei (2020), students preferred having instructors in the middle of the class, but this was not the preference of instructors. The goal is to find a balance that works for everyone.

- Large classes: In large enrollment classes, instructors can ask tables what they think as a group rather than approaching each individual student (McCorkle, 2021).

- Ask for early feedback: Survey or poll students early in the semester to ask about their experience in the ALC. Follow up by sharing the results with the class and addressing why or why not certain requests will be accommodated (Razaei, 2020).

- Teaching persona: Each instructor has a unique teaching style. There is no reason to change your teaching personality in the ALC. In a case study by Chacon-Diaz (2020), instructors teaching in ALCs leaned into their strengths. One instructor used his high-energy levels to pull students back from discussions. Another used the walking space in the class to pace, which helped him while public speaking.

- Teaching assistants/group facilitators: A TA or facilitator in each group can help clarify instructions and concepts and help learning progress. If a TA is not an option, assign a facilitator in each group (Bent et al., 2020; Razaei, 2020).

References

Ahlstrom, L., & Holmberg, C. (2021). A comparison of three interactive examination designs in active learning classrooms for nursing students. BMC Nursing, 20(59), 1-12.

Allsop, J. Young. S.J., Nelson, E.J., Piatt, J., & Knapp, D. (2020). Examining the benefits associated with implementing an active learning classroom among undergraduate students. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 32(3), 418-426.

Baepler, P. (2021). Student anxiety in active learning classrooms: Apprehensions and acceptance of formal learning environments. Journal of Learning Spaces, 10(2), 36-47.

Bent, T., Knapp, J.S., & Robinson, J.K. (2020). Evaluating the effectiveness of teaching assistants in active learning classrooms. Journal of Learning Spaces, 9(2), 103-118.

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J.A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. George Washington University, ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education.

Chacon-Diaz, L.B. (2020). An explanatory case study of behaviors, interactions, and engagement in an introductory science active learning classroom. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 55(1), 26-40.

Chih-Yuan Sun, J., & Wu, Y.T. (2016). Analysis of Learning achievement and teacher-student interactions in flipped and conventional classrooms. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(1), 79-99.

Chiu, P.H.P, Im, S.W.T., & Shek, C.H. (2022). Disciplinary variations in student perceptions of active learning classrooms. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 1-80.

Clinton, V., & Wilson, N. (2019). More than chalkboards: Classroom spaces and collaborative learning attitudes. Learning Environments Research, 22(3), 325-344.

Copridge, K. W., Uttamchandani, S., & Birdwell, T. (2021). Faculty reflections of pedagogical transformation in active learning classrooms. Innovative Higher Education, 46(2), 205-221.

Flanagan, K.M., & Addy, H. (2019). Introverts are not disadvantaged in group-based active learning classrooms. Journal of College Biology Teaching, 45(1), 33-41.

Fukuzawa, S., & Cahn, J. (2019). Technology in problem-based learning: helpful or hindrance? The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology, 36(1), 66-76.

Gibau, G.S, Kissel, F., & Labode, M. (2019). Starting with the space: Integrating learning spaces and technologies. Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology, 8(1), 17-32.

Hao, Q., Barnes, B., & Jin, M. (2021). Quantifying the effects of active learning environments separating physical learning classrooms from pedagogical approaches. Learning Environments Research, 24(1), 109-122.

Holec, V., & Marynowski, R. (2020). Does it matter where you teach? Insights from a quasi-experimental study on student engagement in an active learning classroom. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 8(2), 140-64.

Kugler, A.J. Gogineni, H.P., & Garavalia, L.S. (2019). Learning outcomes and student preferences with flipped vs lecture/case teaching model in a block curriculum. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 83(8), 7044. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6900813/

Leary, M. Tylka, A., Corsi, V., & Bryner, R. 2021. The effect of first-year seminar classroom design on social integration and retention of STEM first-time, full-time college freshman. Education Research International. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/edri/2021/4262905/

Lee, K., Dabelko-Schoeny, H., Roush, B., Craighead, S. & Bronson, D. (2019). Technology-enhanced active learning classrooms: New directions for social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(2), 294-305.

Mantooth, R., Usher, E.L., & Love, A.M.A. (2021). Changing classrooms bring new questions: environmental influences, self-efficacy, and academic achievement. Learning Environments Research, 24(3), 519-535.

McCorkle, S. (2021). Exploring faculty barriers in a new active learning classroom: A divide and conquer approach to support. Journal of Learning Spaces, 10(2), 14-23.

Metzger, K.J., & Langley, D. (2020). The room itself is not enough: Student engagement in active learning classrooms. College Teaching, 68(3), 150-160.

Murphy, M.P.A., & Groen, J.F. (2020). Student and instructor perceptions of a first year in active learning classrooms: Three lessons learned. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 8(13), 41-49.

Rands, M.L., & Gansemer-Topf, A.M. (2017). The room itself is active: How classroom design impacts student engagement. Journal of Learning Spaces, 6(1) 26-33.

Rezaei, A. (2020). Groupwork in active learning classrooms: Recommendations for users. Journal of Learning Spaces 9(2), 1-21.

Stalp, M.C., & Hill, S.E. (2019). The expectations of adulting: Developing soft skills through active learning classrooms. Journal of Learning Spaces, 8(2), 25-40.

Talbert, R., & Mor-Avi, A. (2019). A space for learning: An analysis of research on active learning spaces. Heliyon, 5(12).

Wu, S.P.W., Van Veen, B., & Rau, M.A. (2020). How drawing prompts can increase cognitive engagement in an active learning engineering course. Journal of Engineering Education, 109(4), 723-742.

Young, B., Hynes, W., & Hynes M. (2021). Promoting engagement in active-learning classroom design. Journal of Learning Spaces 10, (3), 13-27.