Course Outcomes & Objectives

- DSI CLEAR

- Teaching Resources

- Theory & Practice

- Methods for Continuous Improvement

- Using AI in the Higher Education Classroom

- Invisible Labor and Faculty Retention Since COVID-19

- Inclusive Discussions

- Inclusive Assessment

- Designing Assessments for Academic Integrity

- Inclusive Instructional Strategies

- Instructor Presence in the Online Classroom

- Tips for Providing Personalized Feedback to Students

- Course Design for Student Retention

- UNT's CLAW 3 Active Learning Classroom Instructional Guide

- UNT Faculty Teaching & Learning Resource Guide

- Growth Mindset in the Higher Education Classroom

- Course Outcomes & Objectives

- Multimedia Course Design for Student Engagement and Retention

- Level Up Learning With Portfolios

- Group Work in Higher Education: Benefits & Practices for Success

- Open Educational Resources & Copyright Essentials for Instructors

- Evaluating OER Resources

- Accessibility Online

- Copyright Guide

- Online Teaching

- UNT Syllabus Template

- Teaching Consultation Request

- Open Educational Resources & Copyright Essentials for Instructors

- Evaluating OER Resources

Assignment Alignment with Course Outcomes

To maintain a standard level of knowledge within disciplines, every course is established around outcomes that determine what students will be able to know or do by the end of the course. These outcomes serve as a foundation on which unit-level objectives, learning activities, and assessments are all built upon and designed to help students achieve the course-level outcomes. The following content describes how assessments and learning activities support course-level outcomes and unit-level objectives using key concepts and course design frameworks.

Course-Level Outcomes, Unit-Level Objectives and Learning Activities and Assessments

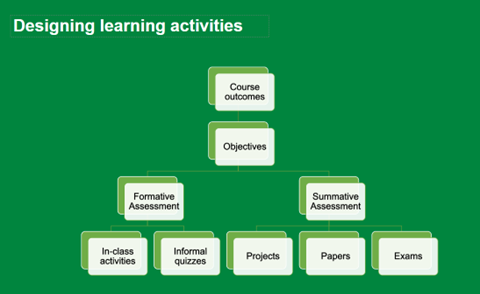

The image above illustrates the hierarchy of course outcomes to assessments in a simple flow chart. Course-level outcomes are at the top, unit-level objectives are directly below it, branching out underneath unit-level objectives are formative and summative assessments. Under formative assessments, in-class activities and informal quizzes branch out. Under summative assessments, projects, papers, and exams branch out.

Course-Level Outcomes and Unit-Level Objectives

Course-Level Outcomes are the outcomes that students can expect to see and achieve by the end of the course and typically apply field theory to practice or occupational skills. Unit-Level Objectives are course-level outcomes broken down into incremental building blocks that guide each individual module or unit throughout the course. Unit-level objectives scaffold in a way that enables students to meet the course-level outcome by first building on their foundational knowledge or a given subject. Module by module, students meet each subsequent unit-level objective and eventually, through their cumulative success, will achieve the course-level outcomes.

When thinking of course-level outcomes and the unit-level objectives that build up to them, instructors should ask themselves these three questions:

- Is this outcome measurable?

- Is this outcome appropriate?

- Is this outcome specific?

It is difficult to measure student success when expectations are poorly defined. Consider the rubric. A rubric is a distinct set of guidelines that clearly state how many points will be awarded to students for meeting certain standards or criteria. They are a tool for measuring success in an assignment. Course-level outcomes and unit-level objectives must also be measurable and specific.

For example, if a course-level outcome in a statistics course was simply “students will be able to use statistical methods to describe data,” then it is difficult to see what success would actually look like. What specific statistical methods are students meant to perform by the end of the course? What are they doing with the data? Rather, the outcome, “Students will be able to successfully perform statistical operations such as generating descriptive statistics, determining significant relationships between data, and illustrate statistical relationships using bar charts” describes specific knowledge and skills.

Learning Activities and Assessments

Learning activities and assignments are where the learning happens. Learning activities and assignments, when inclusive of all students regardless of cultural, psychological, or neurological contexts, can take the form of low-stake assessments that allow students to “fail forward” (Addy, 2021; Meyers et al., 2019) without impacting course grade. This might look like short weekly quizzes with low point values or weekly discussion posts where the two lowest grades are dropped. This allows students to learn from their mistakes and do better on future learning activities and assignments (Addy, 2021; Meyers et al., 2019). Part of inclusive teaching and course design is understanding students' potential and ability with a growth mindset, which states that people are not inherently good or bad or more or less intelligent than one another (Dweck, 2017). Rather, everyone can learn and grow their abilities and knowledge across different subject areas (Dweck, 2017). This means all students can achieve the unit-level objectives and course-level outcomes through the right approaches to teaching and learning for them.

Let’s say that the course-level outcome for students in a sociology course is to “Understand and apply Bourdieu’s field theory to labor and various occupational fields.” Appropriate unit-level objectives that contribute to this course-level outcome might be “Outline Bourdieu’s field theory”; Identify three types of capital as described by Bourdieu”; and “Examine an occupation through using Bourdieu’s theoretical framework of field theory.” These unit-level objectives work together to help students reach the course-level outcome of understanding and applying Bourdieu’s field theory to practice. Learning activities and assessments that may support these objectives and outcome could include short low-stake essay questions or discussions about Bourdieu’s field theory and how it may apply to certain occupations.

Bloom’s Taxonomy

A tool frequently used by instructors for course design is Bloom’s Taxonomy, which is a framework that engages cognitive processes from “lower order” thinking skills to “higher order” thinking skills that students will experience throughout their course (Armstrong, 2010). The basic idea behind Bloom’s Taxonomy is that when a student learns new information and skills, there is a predictable order of “steps” they will make from foundational knowledge to applying that knowledge in new situations (Armstrong, 2010). The goal is for students to achieve autonomy in this newfound knowledge and skills through deep understanding, so that as they move “up” the steps of the pyramid, they can analyze the whole by breaking it into parts (Armstrong, 2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy defines six levels of cognitive processes as described by Armstrong (2010):

- Level 1: Remembering, retrieving, and recalling information

- Level 2: Understanding and demonstrating comprehension

- Level 3: Applying new information to real-world situations

- Level 4: Analyzing parts of a whole

- Level 5: Evaluating information through a process of applying criteria

- Level 6: Creating and use knowledge or skill in a new situation.

When deciding on course-level outcomes and unit-level objectives, consider what level students are on in a given subject area (Colorado College, 2022). Are they brand new to the subject coming into an introductory course, or have they already gained some foundational knowledge and understanding through pre-requisites that have allowed them to complete the first two levels, and are now ready for a course that brings them to level three? For example, in an Introduction to Archaeology course, it would not be appropriate to task students with writing a dissertation and conducting field research in the desert, as students who are new to archaeology will be in levels one and two, and not ready for levels three through six. Using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a reference, instructors will know to assess what level their students are at which then informs what outcomes and objectives to set for them, and what sort of learning activities and assessments will best contribute to their learning in a meaningful way.

Bloom’s Taxonomy does not only focus on high-level outcomes and objectives but can be useful for designing learning activities and assessments as well. Bloom’s Taxonomy contains a list of verbs that can give instructor’s ideas for how to approach learning activities and assessments. For instance, verbs students can use to demonstrate learning at an introductory level might be to define, describe, recognize, explain, and illustrate basic archaeological concepts (Colorado College, 2022). Students in level six would be better suited to conducting something like dissertation research, which could utilize the verbs develop, invent, write, and design (Colorado College, 2022).

In summary, using Bloom’s Taxonomy is a useful tool to create course-level outcomes and unit-level objectives that fit your student population, and to develop appropriate activities and assessments to support student mastery.

Backward Course Design and Alignment

The framework of backward course design ensures alignment between learning activities and assessments and the chosen course-level outcomes and unit-level objectives (Davis, Gough, & Taylor, 2021). A carefully aligned lesson will ensure the learning experiences and assessments support your course-level learning objectives and unit-level objectives (Davis, Gough, & Taylor, 2021).

Backward course design is unique from content-focused course design, which builds the course around the textbook being used because it begins with the end results in mind, such as the course-level outcomes students will work towards mastering (Davis, Gough, & Taylor, 2021). When using backward course design, consider the following questions:

- What is most important for students to know, and why?

- What is worth being familiar with your course and discipline?

- What is important for all students to know and do regardless of major or career?

- What are the ways in which any student could benefit from what you have studied in your discipline?

- Finally, what knowledge and abilities do you want your students to walk away with at the end of the lesson?

With these questions as a guideline for choosing course-level outcomes, focus is shifted away from textbook content and onto student’s development of specific knowledge and skills.

Backward course design follows these three steps as described by Davis, Gough, & Taylor (2021):

- Step 1: Determine what students should get out of the course via student learning outcomes given their level of knowledge and ability in the subject. Think back to Bloom’s Taxonomy and the different levels of cognitive processes students are at depending on how much they have already learned within the discipline. Are they entry-level students where every concept is new? Or are they experienced senior- or graduate-level students who are ready to apply what they’ve learned to novel situations? Understanding the student’s knowledge and skill level allows instructors to construct a meaningful and appropriate course.

- Step 2: Determine how to assess whether students have achieved the learning outcomes or unit-level objectives. Use assessments that would best demonstrate student’s progress toward meeting these outcomes and objectives. For example, in a statistics course, an appropriate assessment would be to have students run basic statistical analyses in programs such as SPSS to demonstrate their understanding of, and competence in using, statistical methodologies correctly.

- Step 3: Design learning experiences around assessment tasks. The learning experiences you present for students should prepare them for the assessments, which in turn help students achieve the course-level outcomes or unit-level objectives.

This intentional and relational strategy for structuring a course around course-level outcomes is the core component of backward course design. This will put outcomes, objectives, learning activities and assessments in alignment with one another and in support of one another, creating a logical learning pathway for student success.

Conclusion

Course design starts with understanding your student population, what it is they are capable of understanding or doing by the end of the course, and how to incrementally get them there throughout the semester using strategically designed unit-level objectives, learning activities, and assessments. Bloom’s Taxonomy and Backward Course Design are foundational building blocks to designing a well-aligned course and appropriately measuring student learning. Every component of the course is connected and works together in conjunction to guide students to the desired destination.

References

Addy, T.M., Dube, D., Mitchell, K.A., & SoRelle, M. (2021). What Inclusive Instructors Do: Principles and Practices for Excellence in College Teaching, Stylus Publishing.

Meyers, S., Rowell, K., Wells, M., & Smith, B.C. (2019). Teacher empathy: A model of empathy for teaching for student success. College Teaching, 67(3), 160-168.

Dweck, C. S. (2017). From needs to goals and representations: Foundations for a unified theory of motivation, personality, and development Links to an external site.. Psychological Review, 124(6), 689-719.

Armstrong, P. (2010).Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.Colorado College, 2022

Davis, N. L., Gough, M., &Taylor, L. L. (2021). Enhancing online courses by utilizing "backward design." Links to an external site. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 21(4), 437-446.

Colorado College. (2022, April 14). Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy. Assessment. https://www.coloradocollege.edu/other/assessment/how-to-assess-learning/learning-outcomes/blooms-revised-taxonomy.html